African Lit Review: “The Dreamer and the Badass”: The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah

February 28, 2019

by Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed, Founder, bookshy

“Aminah is a bit of a daydreamer”, Ayesha Harruna Attah explains to the packed room at Politics and Prose at The Wharf in Washington DC. Attah goes on to speak about Wurche, “a princess in the region of Salaga [in now Northern Ghana]. A badass, rides her horse, wears men’s smocks, wears her hair short, wants to take an active role in her father’s court, speaks Arabic [and] wants her father to take her seriously.”

With these words, we are briefly introduced to these two women in pre-colonial Ghana whose lives intersect in Ayesha Harruna Attah’s third novel, The Hundred Wells of Salaga.

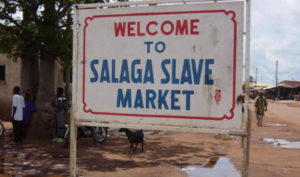

Salaga – a trading town in pre-colonial Ghana

Salaga – a trading town in Gonja in pre-colonial Ghana – was known as “the Timbuktu of the South”. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Salaga served as a key market town for the Asante kingdom, particularly for the busy inter-regional kola trade to Hausaland. This was until the Asante defeat of 1874, which cut Salaga off from the kola trade. As the kola trade declined, slave trading became even more important, as large numbers of slaves were transported by enormous caravans to Salaga before being sold in towns and villages in the interior and the coast mostly for internal slavery, but also across the Atlantic.

Credit: My Joy Online

The Hundred Wells of Salaga’s extremely rich story is also set against an important political backdrop. Although Britain had already passed its Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833, abolition in all its colonies was gradual, and the smuggling of slaves did not end entirely until Brazil finally enacted emancipation in 1888. The Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885 (or the Scramble for Africa), where various European powers competed for territory in Africa by dividing, conquering and exploiting, had already happened. Additionally, between 1889 and 1899 – the colonial powers of Germany (coming from Togoland) and Britain (coming from the Gold Coast), considered the disputed territory of Salaga between their colonies as neutral. Also, important is the political system of a “rotating chieftaincy” among royal members from different clans in the region Salaga was located.

“The Dreamer and the Badass”

Aminah and Wurche, are two contrasting characters, leading extremely different lives when we first meet them.

Aminah, fifteen and stunning, is from the village of Botu – one of the stops for caravans en route to Salaga. Along with her younger twin sisters, she sells food to those resting there before continuing their journey. Raids are also happening, and Aminah and her twin sisters are captured in one of them and enter the domestic slave trade – sold to a farmer who then sells Aminah at Salaga market.

In sharp contrast to Aminah is Wurche – the daughter of Etuto (a lesser chief of Kpembe, contesting not being able to take his rightful turn as ruler). Wurche is a remarkable woman, who could have been a leader, but Etuto eventually makes her enter a marriage to strengthen the alliance between two neighbouring kingdoms. Wurche is also wary of the supposedly harmless Germans, Brits (and to a lesser extent French) in the Salaga area, informing her father that the Europeans may not be as neutral as they claim to be. Etuto pays no attention, leading Wurche to forge her own path, involving among other things, illicit affairs.

Not to be forgotten is Helmut – a German, who Wurche gets close to and is able to observe and gain more insight on Europeans real intentions, and Moro – a slave raider, who was also born into slavery, and in an interesting turn of events ends up having a connection to both Aminah and Wurche.

“I knew I had the novel the minute I heard about this ancestor.”

“Aminah”, Attah explains during the reading, “is inspired by my great great grandmother”. While working on her family tree, her father mentioned there was a ‘slave daughter’ on his maternal side. Attah’s father was able to share the little he knew of this ancestor: she was beautiful, could have been from Burkina Faso, Mali or Niger, had skin that was reddish-orange in colour, and ended up in Salaga. Attah wanted to know more, but faced a roadblock: “Nobody would talk about it”. Her solution, “fictionalise it”.

Aminah may have been nested in fiction, but Wurche is steeped in reality – named after Burugu-Wurche, the Queen of Burugu in Gonja in the seventeenth century. As Attah rightly states, ‘“I don’t think Wurche was unusual”. Africa in the fifteenth to seventeenth century had women in positions of authority, such as Queen Amina of Zazzau who conquered cities as far as Nupe, and also ruled Kano and Katsina for 34 years. Yet, written historical texts at that time largely focused on men (and male leaders). Queen Amina was briefly mentioned in the Kano Chronicles (an account of Kano History compiled largely from oral sources during the reign of Emir of Kano Muhammad Bello [1882-93]), as the first to obtain kola nuts in Hausaland – a tribute from the chief of Nupe.

“She is remembered as ‘the slave’”, and “I hope I did her right in writing this”.

The Hundred Wells of Salaga is a slim book, but Attah is a gifted storyteller who paints a vivid and rich picture of pre-colonial Ghana it feels like she must have been alive at the time – raiders capturing and enslaving people for the slave trade, the politics within the region between the different clans, the influence of Islam in West Africa, the genesis of what would become the Salaga Civil War in 1892, and the Europeans trying to stake their own claim across the continent.

Attah is also able to capture the everyday lives of women, and this is one of the areas where the book truly excels. By putting women, their narratives and experiences at the centre of this critical period between the ending of slavery and the beginning of colonialism, we are introduced to the more intimate aspects of life – sexual relations, love, extramarital affairs, abuse, the fight for freedom – to address our historical knowledge gaps.

The Year of Return

The US launch of The Hundred Wells of Salaga comes at an interesting point in time – Year of Return, Ghana 2019, marking the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Africans in the English colonies at Point Comfort, Virginia, in 1619, and an opportunity for Africans in the Diaspora to connect with Africans on the continent. The significance of this act of acknowledgement and commemoration is momentous and a beautiful thing.

I will admit, I have been following The Year of Return superficially. If you’re like me – and on Instagram – your timeline would have been flooded with images and Insta stories around December 2018 and January 2019 of celebrities getting turnt in Accra. There’s also the focus on boosting tourism. Nothing wrong with that, but will The Year of Return also be used as an opportunity to fully embrace our complex and contradictory history? To not downplay the actions of Africans in the slave trade – something Attah does not shy away from in this novel, albeit through internal slavery – and start a larger dialogue on slavery (a practice that still continues even today in many parts of the African continent).

DC was the fifth stop on The Hundred Wells of Salaga US tour, with Aminatta Forna – who Attah was in conversation with – asking how the book had been received so far in America. Attah spoke about an African American woman at a reading in New York who had been unable to truly connect with Africa, as much as she wanted to, because of the complicity of Africans in the capturing and selling of other Africans into the slave trade. Attah felt The Hundred Wells of Salaga was “her apology book” to the African Diaspora.

Credit: Ayesha Harruna Attah Instagram

I also wanted to know the reverse – how the book, first released in a number of West African countries and the UK in May 2018 by Cassava Republic Press, had been received, particularly in Attah’s home country of Ghana. Attah explained the responses were: “We had no idea”, “I didn’t know this existed”. Attah sees this differently, “We closed our eyes to the reality – the truth. We just didn’t. Correction, I didn’t admit it, until it hit close to home.”

This “selective blindness” and silence among Africans to slavery (internal and Trans-Atlantic), and the difficult and painful conversations that need to be had between Africans and the African Diaspora is something Attah hopes the book can kick-start. It can do this by opening the door to begin much needed dialogue about this extremely important part of African and Black History. Certain things can no longer be ignored, and The Hundred Wells of Salaga shows the power of fiction in confronting our past and not-so-hidden histories.

The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah | Other Press | Feb 5, 2019

Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed is a Senior Technical Advisor on Women’s Rights. Zahrah is also the founder of the African literary blog, bookshy. She holds a BSc in Human and Physical Geography from University of Reading, an MSc in Urbanisation and Development and a PhD in Human Geography and Urban Studies, both from London School of Economics (LSE).